Kent County’s Eastern Neck Island became a 2,285-acre national wildlife refuge in 1962. Quite likely Captain John Smith and his men observed the island—maybe even landed on it—during their exploration of Chesapeake Bay in the early 1600s. Native Americans lived there at the time, as they had since time immemorial.

In late winter 2009, Jonathan Priday, then-refuge manager, stumbled across an old wooden skiff stashed in a pole shed on Cedar Point, resting on the bare ground and tangled in briars. “Looks decrepit, but solid,” he told me, and I quickly drove out to see it. (At the time, I was president of Friends of Eastern Neck.)

An old wooden rowboat was resting on the ground, partly exposed to the weather, spattered with mud, encased in briars, and partially filled with leaves and debris. Long and narrow, it was built rough, like nothing you see on the water these days. An obvious relic.

We put in a call to Pete Lesher, curator of collections at the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum in St. Michaels, and he expressed intense interest.

Inspecting the skiff a few days later, Lesher said he thought it was a gunning skiff likely built by Ira Hudson of Chincoteague, Virginia, in the 1910s or ‘20s. He instructed us firmly: “Don’t do anything to it. No restoring! Leave it as is!” Shortly after, Jonathan mustered some fellow U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service staff to help move it into a dry shed. Brushed clean of debris, there it sat, safely on sawhorses.

Moving ahead to 2012, Melissa Baile, a Friends board member, and Terry Willis, a long-time refuge volunteer, proposed that a display structure be built to house and exhibit the skiff properly. The board voted to allocate the funds, drawings for a suitable shed were offered by architect John Donnelly, and the shed was constructed by builder Jay Yerkes.

We sponged the skiff out and tidied it up as much as possible, and another Fish & Wildlife crew gently trundled it from storage into her new home. By this time, Priday had been transferred to a new post in Alaska and the refuge was being managed by Cindy Beemiller, who coordinated and supervised the operation.

A story in the Kent County News by reporter Craig O’Donnell about the skiff and its new display structure then caught the eye of Joe Walsh. Joe’s father, Dr. Harry Walsh, was the author of a local history, “The Outlaw Gunner,” and the Walshes are long-time residents of Easton, in Talbot County.

Joe telephoned to tell me he had a hunch the skiff at Eastern Neck was once part of his father’s extensive waterfowl-hunting collection of wooden boats, market guns, shotguns, decoys, and traps. Dr. Walsh had donated his collection to the national wildlife refuge at Chincoteague in 1969.

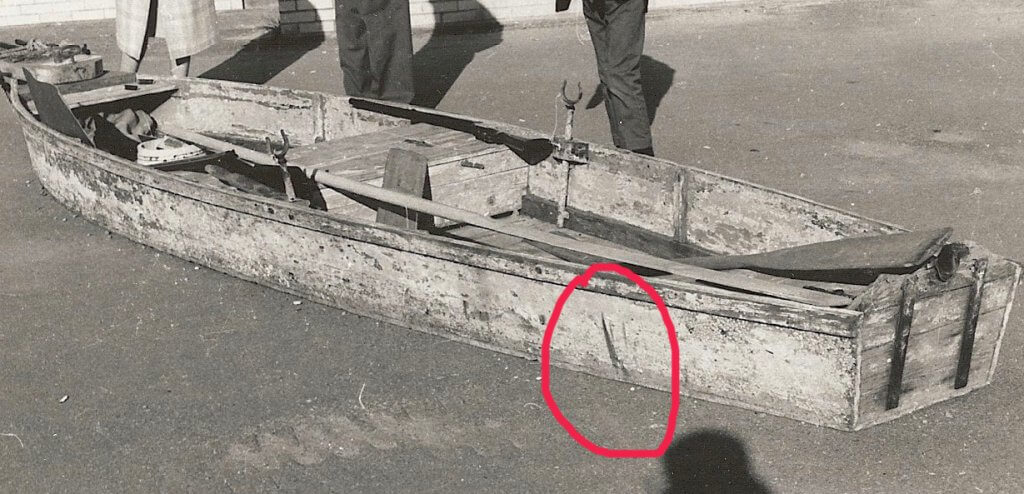

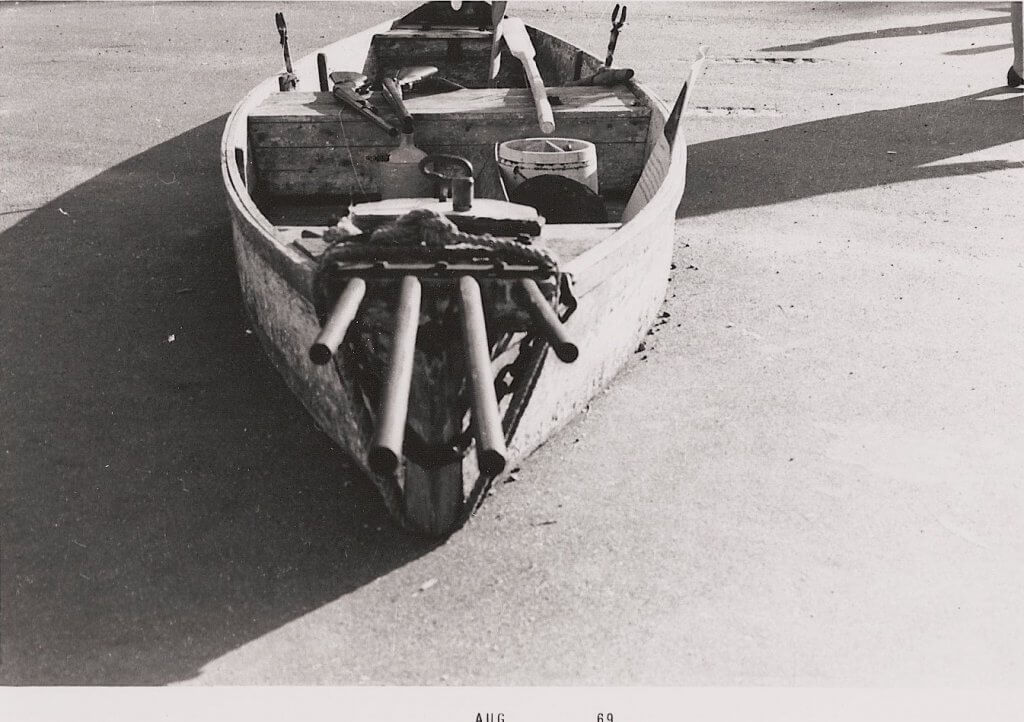

Joe sent me several black-and-white photos of the skiff taken by his father in August of 1969. Excited, I drove to the refuge and lo and behold! The markings in the photos and on the skiff itself were exactly the same! Joe was right, it was indeed his father’s old skiff!

This also confirmed that the skiff in the photo on page 116 of “The Outlaw Gunner” is the very same boat. Dr. Walsh’s book documents the practice of outlaw gunning—or market gunning—by locals who illegally hunted and sold ever-diminishing numbers of waterfowl on Chesapeake Bay a century ago.

So, how did Eastern Neck’s skiff end up unceremoniously stashed in that pole shed on Cedar Point? The last piece of the puzzle was supplied by Kenneth Fletcher, a long-time Rock Hall resident. Ken told me that while he was employed at the refuge, he was told to truck the skiff from Chincoteague to Eastern Neck. “I think that was in 1969. It could have been later, but not much,” he said. He also remembered storing the skiff in the pole shed sometime in the early ‘70s.

Joe Walsh visited the Refuge to inspect the skiff for himself, and agreed that it’s the same boat that disappeared after 1969, only to reappear in 2009.

Dr. Walsh’s papers bear out the accuracy of Pete Lesher’s early guess that the skiff was built by Ira Hudson, who was also a skilled decoy carver in Chincoteague. The papers also report it was built in 1917. Walsh acquired the skiff for his extensive collection and decided to donate it to the Chincoteague Refuge for its museum (which never became a reality). It was transported to Eastern Neck, put on exhibit for a while, and then stored for the better part of 40 years in that obscure pole shed on Cedar Point.

After the July 2012 dedication ceremony for the skiff in its new display structure next to the former hunting lodge that serves as the refuge headquarters—for which Joe Walsh and several of his family cut the ribbon—he wrote me in a letter:

“I am sure this is the same boat from Dad’s book. It strikes me as funny that after 40-plus years, the boat finally ends up on display as my Dad had intended, and only a few miles away from where he grew up as an outlaw gunner.”

For more information:

- “The Outlaw Gunner,” by Harry M. Walsh (paperback)

- Article in Kent County News: https://www.myeasternshoremd.com/news/kent_county/antique-gunning-skiff-displayed-at-eastern-neck/article_8355ab80-c7a0-11e1-b9ef-001a4bcf887a.html

- Article on Ira Hudson: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ira_Hudson

Cover photo: Gunning skiff in display case at Eastern Neck National Wildlife Refuge.

Photo: Leann Miller.