I had the best time last weekend! I counted birds in our backyard, as part of the Great Backyard Bird Count (GBBC). A yearly event in mid-February, this count is famous among birders, and promoted by bird organizations worldwide. This year’s count was February 12-15.

The GBBC began in 1998 when the Cornell Lab of Ornithology and National Audubon Society launched the count as the first online citizen-science project. Its purpose is to collect data on wild birds and to display results in near real time. Oiseaux Canada (Birds Canada) joined up in 2009 to promote participation in that country, and in 2013 GBBC became a global project with the introduction of eBird (another citizen science project) as a data reporting tool.

What is citizen science? The Citizen Science Association defines citizen science as “the involvement of the public in scientific research — whether community-driven research or global investigations.” They claim there are over 2,000 active citizen science projects, and over one million volunteers working on them.

The concept is not a new one. The National Weather Service has run the Cooperative Observer Program to collect data on meteorology and climatology since 1890, enlisting the help of ordinary people to record daily weather. The Audubon Christmas Bird Count, started in 1900, has provided a long historical record of winter birds in the U.S.

The first citizen science project I heard of (that described itself in those terms) was the SETI@home project — the Search for Exterrestrial Intelligence. Hosted at the Space Sciences Laboratory at the University of California, Berkeley, the goal of this project, started in 1999, was to discover radio evidence of extraterrestrial life. Volunteers with an internet-connected computer ran a free program that downloaded and analyzed radio telescope data. The project went into hibernation in March 2020, with over 98 percent of the sky still to be surveyed, but back-end data analysis continues. And the search goes on, with promises of more citizen science involvement opportunities to come.

Testing water quality. Pixnio.

Measuring snow. Wikimedia Commons.

Flying ants. Wikimedia Commons.

Koala. Wikimedia Commons.

Road sign. Wikimedia Commons.

Old dog. Pixabay.

There are a wide variety of scientific projects that depend on the observations of ordinary people. Weather and wildlife are popular subjects. There are projects to measure snow in the U.S., count koalas in Australia, and report on flying ants in the U.K. There are three projects that are studying roadkill data for insights into wildlife movements and traffic safety — two in Europe and one in Taiwan. “Did You Feel It?” is a U.S. Geological Survey project to record the extent of earthquakes. There are thousands of water quality projects in the U.S. since 1969. But there are also interesting projects in other disciplines, such as the Lingscape project that asks volunteers in Europe to take photos of road signs for a database of languages used on signs; the Litterbug project, also in Europe, that collects data on (you guessed it) litter; and the Dog Aging Project at the University of Washington. Any area where the scientific record requires more data than can be generated by a few scientists is a good candidate for citizen involvement.

But I digress.

Like the other projects mentioned, the power of the GBBC is in the sheer amount of bird-sighting data that is reported for the four-day period. In 2020, over 268,000 people participated, individually or in groups, by watching and recording birds for at least 15 minutes. Those volunteers submitted almost 250,000 checklists and recorded over 6,900 different species of birds worldwide. Checklists for 2021’s count are still being submitted through the end of the month, but indications are that those numbers will be surpassed. On the most basic level, these bird counts give us information about what kinds of birds inhabit different areas, such as cities and suburbs compared to more natural habitats.

But the importance of the GBBC is not solely found in any one year’s data, for scientists can look at trends in year-over-year data. The information from GBBC participants, combined with other surveys, helps scientists learn how birds are affected by environmental changes. GBBC data can show the first indications that individual species may be increasing or declining from year to year. Data gathered over many years help highlight how a species’ range may be expanding or shrinking, or how a species may or may not be adapting to changes in their environment.

I was a citizen scientist for all four days. I counted birds in the backyard in the morning, and then again in the afternoon. The rules are simple. Count for at least 15 minutes. Record the highest number of individuals of each species seen at one time during the observation period. Submit a separate checklist to eBird for each counting period. And if you can’t identify a bird, there’s an app for that!

I saw a lot of birds over the four days. Part of the reason for this is that we had snow on the ground, and more birds are drawn to the feeders — and under the feeders — when natural food sources are covered by snow. I saw all the regulars and then some.

American Goldfinch. Pxhere.

Pine Siskin. The Salmons.

House Finch and Goldfinch. Beau Considine, Flickr.

Dark-eyed Junco. Pixabay.

Mourning Dove. Snappy Goat.

Red-winged Blackbirds. USFWS, Hollingsworth.

There were large groups of finches (American Goldfinches, Pine Siskins, House Finches) at the sunflower and thistle feeders, busy bands of Dark-eyed Juncos and Mourning Doves on the ground, and sizeable crowds of mixed blackbirds (European Starlings, Red-winged Blackbirds, Brown-headed Cowbirds, Common Grackles) under the sunflower seed feeder and worrying the suet.

Red-bellied Woodpecker. Wikimedia Commons.

Carolina Chickadee. Pxhere.

Carolina Wren. Pixabay.

Northern Cardinals. Korwel Photography.

White-throated Sparrow. Wikimedia Commons.

Downy Woodpecker. Korwel Photography.

There were solitary Red-bellied Woodpeckers on the suet, and lone Carolina Chickadees, Carolina Wrens, and Tufted Titmice zooming to the sunflower seed feeder. The Northern Cardinals arrived as a couple, as did the White-throated Sparrows and House Sparrows, and sometimes Downy Woodpeckers.

Red-breasted Nuthatch. Wikimedia Commons.

Red-breasted Nuthatch. Author.

The Red-breasted Nuthatch was on the eBird list as rare for Rock Hall in February, but there have been at least two eating our seeds since the fall, so they weren’t rare to me. I made sure to describe appearance and behavior so a list reviewer would believe me, and I finally was able to take a very bad and grainy picture to submit on the last day.

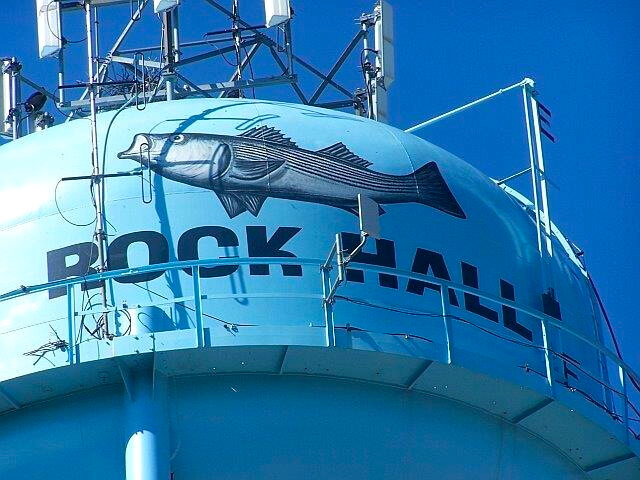

Water tower with no eagles. Walter Shook.

Two eagles, not on water tower. Picryl.

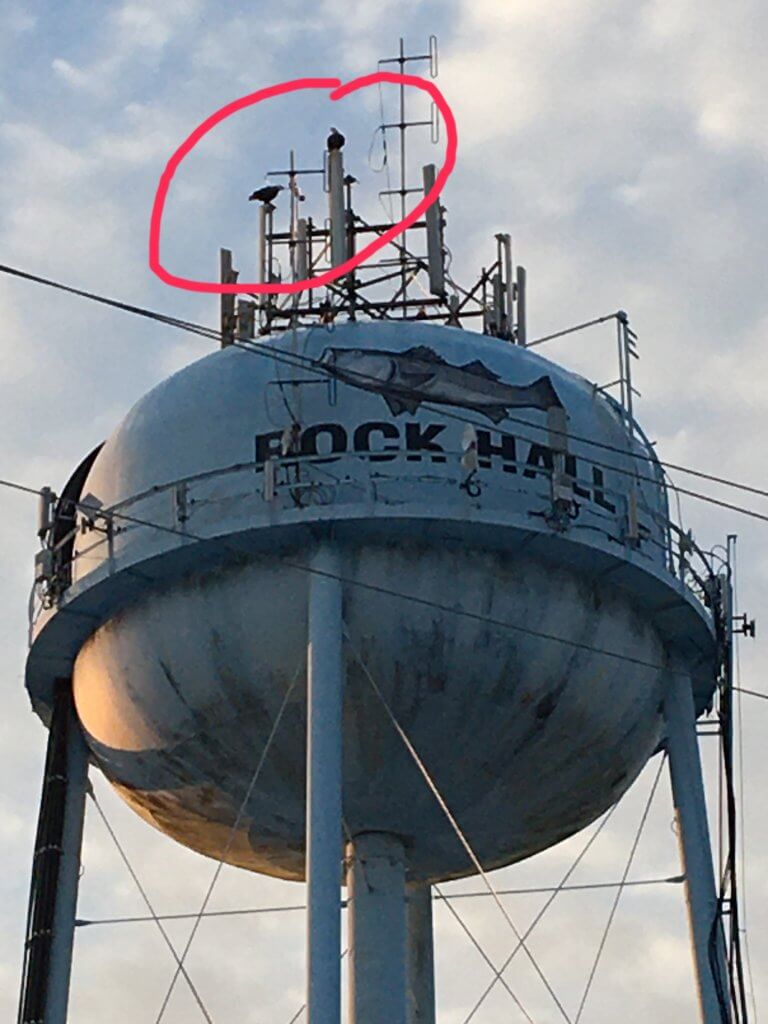

Two eagles on water tower. Author with cell phone, again.

I also reported the two Bald Eagles that come every day to sit on the water tower across the street; they sing to each other and it’s so sweet.

A Cooper’s Hawk flew in to check out the feeders for a lunchtime meal one day, but flew away hungry.

A small V of Canada Geese flew over one day, and several Turkey Vultures soared overhead. We get gulls flying overhead all the time, so I reported those as gull species unknown since they were too far away to identify.

My numbers: I reported 21 species. On eight checklists I reported 477 individuals, but, of course, I was reporting the same birds over and over and over again. I am ranked 25,071 of all participants in number of species reported.

Counting birds for the Great Backyard Bird Count was fun, and a great way to spend some time for the common good. I’ll do it again.

Cover photo: Tufted Titmouse, via Pixabay.