Most Eastern Shore towns have many excellent examples of American Foursquare houses. But I didn’t realize that until I began looking specifically for them. Why hadn’t I noticed them? Maybe because most of them are not flashy or showy like their older Victorian neighbors. Maybe because they’re not eye-catching like their cute bungalow cousins. Or maybe I’m just not that observant. But they’re there.

Foursquares were a popular choice because they were simple, clean, and economical to build. They enabled a lot of middle-class families to become homeowners. Their interior layouts offered large rooms and multiple bedrooms, perfect for families. They fit well on smaller city and town building lots, although they were also built as farmhouses. They were easily expanded with additions. And, in an era of porch-sitting, they had lovely large covered front porches.

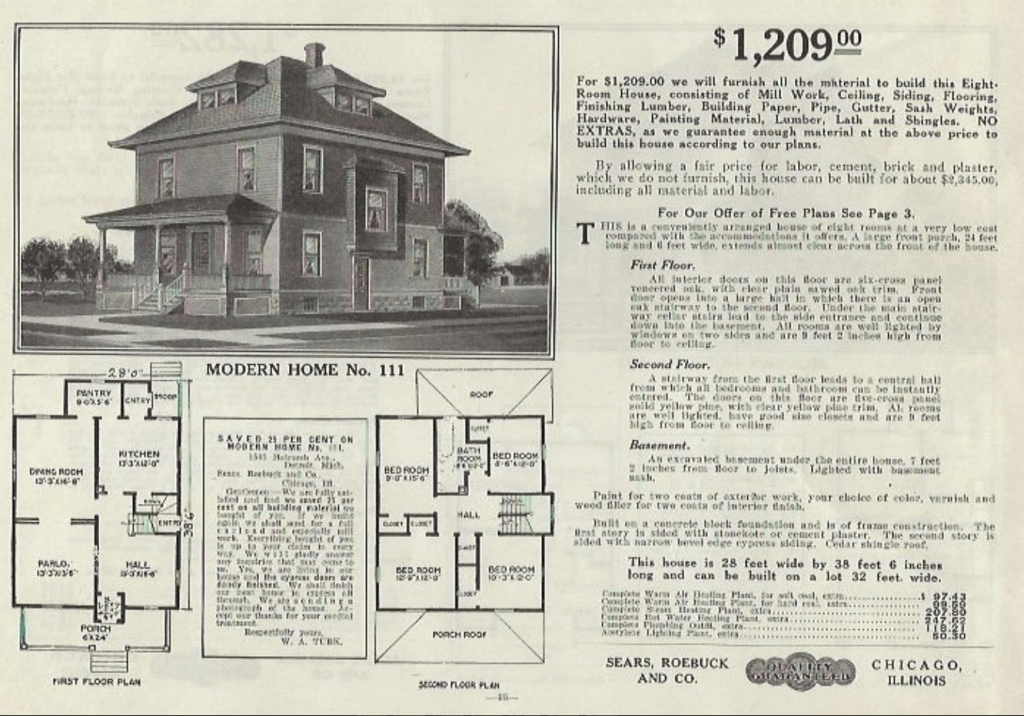

The American Foursquare house was popular from the mid-1890s to the late 1930s, and they were constructed all over the country. They were intentionally plain, as a reaction to the over-decorated Victorian gingerbread houses of the 19th Century. The typical foursquare house is a square box, with two-and-a-half stories, a pyramidal hipped roof, front dormer, and large covered front porch with steps. They can be built of almost anything from wood frame to brick to concrete block to stucco.

Foursquare houses were built in many styles — especially Craftsman, Mission, and Prairie — and incorporated exterior and interior architectural elements of those styles. But most often they were left plain.

There are usually four main rooms per floor. A typical floor plan has a large front entry hall with stairs to the second floor and a living room in the front, and a dining room and kitchen in the back, all on the four corners. There are four bedrooms on the second floor at the corners, and a bathroom and stairway in between. And a third floor open space attic area nestled under the hipped roof.

Historically, houses were purchased with cash, so only the wealthy could buy homes. By the 1890s mortgages were becoming more common, but they were structured differently than today. Most required 50 percent down payments and had terms of three to five years. Monthly interest-only payments were paid until the end of the loan, when the principal was due in total. Borrowers could (and did) renegotiate their loans every year. So home ownership began to expand during the heyday of foursquare construction, but it still required more cash than most people had available.

Mail-order house kits were a solution for many people. The kits were available in many styles and at a range of price points. The foursquare was a popular variety offered by Sears, Roebuck and Co. and Aladdin, the two biggest kit house manufacturers. In the early 20th Century tens of thousands of these “catalog houses” were sold. Kits of pre-cut and labeled parts and directions were delivered in a railroad boxcar; kit houses proliferated in towns with rail lines. Sears offered three lines of homes in hundreds of styles, aimed at customers’ differing financial means. The popular Woodland model was a foursquare, and was sold for $938 in 1916.

Sears homes used mass-produced materials, which lowered purchase costs for customers. Pre-cut and fitted materials saved up to 40 percent in construction time, and the use of innovative construction techniques saved money for homebuyers as well. Modern conveniences such as central heating, indoor plumbing, and electricity were also available as options, spreading the new technologies.

I’ve never been inside an American Foursquare house on the Eastern Shore. But my husband and I lived in one in Baltimore. That is, we lived in a brick rowhouse built in 1918, with the exact floor plan of a foursquare. It was huge! A rowhouse foursquare is a style adaptation that I haven’t seen mentioned in the architectural literature. But we loved our house for all the reasons that made the American Foursquare a popular choice in the early 20th Century.

Cover photo: Frame construction foursquare house in Goldsboro.

Photos by Jan Plotczyk and Gren Whitman