Frederick Douglass and Harriet Tubman, self-emancipated slaves from Maryland’s Eastern Shore, helped John Brown to plan his radical insurrection at Harpers Ferry in 1859. Neither joined the raid, however.

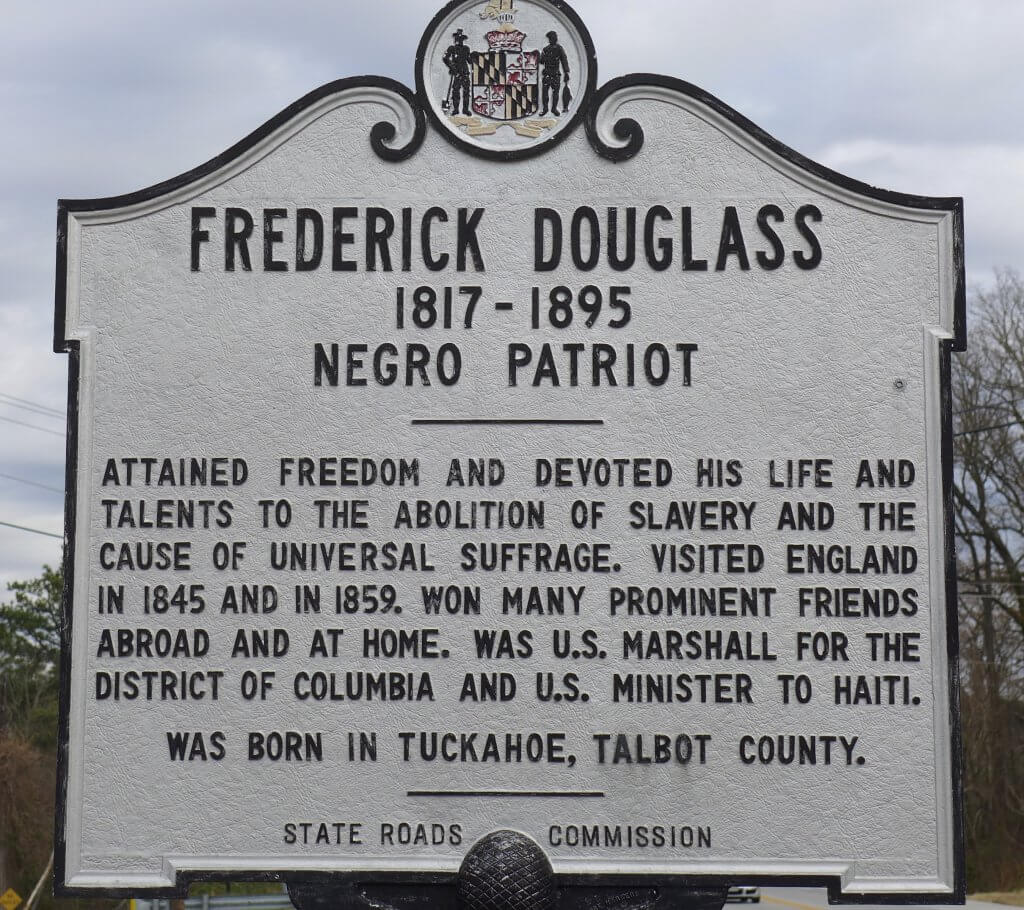

Somewhere between Cordova and Hillsboro near Tuckahoe Creek in Talbot County, Douglass was born into slavery in 1817 as Frederick Bailey. Despite his enslaved status, he learned to read and write at an early age. While working as a shipyard caulker, he escaped to the North. “On Monday, the third day of September 1838,” Douglass wrote in his 1845 autobiography, “I bade farewell to the city of Baltimore and to that slavery which had been my abhorrence from childhood.” He became famous as an orator, fiery abolitionist, and confidant of Abraham Lincoln.

Enslaved from birth in Dorchester County as Araminta Ross in 1821, Tubman was forced to work in timbering and farming during her bitter, hard early years in Tobacco Stick—now Madison—and Bucktown. Suffering a serious head injury when she was 13, she was permanently afflicted with spells and visions. After escaping from bondage in 1849, she returned at least 13 times before the Civil War to Dorchester County to conduct 70-plus relatives and friends to freedom on the Underground Railroad. “On my Underground Railroad,” she said, “I never ran my train off the track and never lost a passenger.”

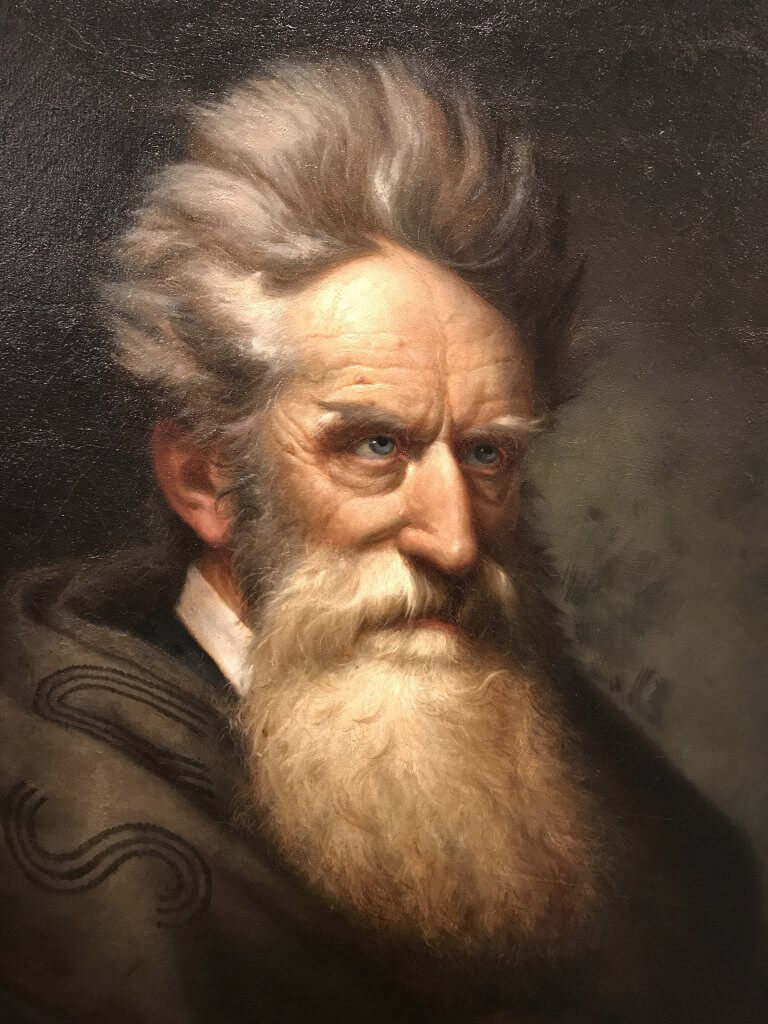

John Brown was born in 1800. A relentless enemy of slavery from an early age, he led a band of guerrilla fighters in several clashes in “Bleeding Kansas” in the late 1850s. At one point, his little force raided a plantation in Missouri, freed a number of slaves, and conducted them hundreds of miles to safety in Canada. For 20 years, he planned to seize the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry and then to establish a liberated zone along Virginia’s Blue Ridge. Extended farther and farther into the South, his mountain fastness would provide refuge for escaped slaves and a “subterranean pass-way” for them to the North.

Tubman and Douglass admired Brown and considered him an ally against slavery. Brown called her “General Tubman” and referred to Douglass as “my friend.” They both knew about and supported his plan to attack and seize the Harpers Ferry arsenal.

Douglass met Brown in 1847, and was privy early on to his plan to attack slavery. Over the years, the two remained in touch, and visited each other’s homes. Douglass said that Brown was “in sympathy a black man and as deeply interested in our cause, as though his own soul had been pierced with the iron of slavery.”

However, while conferring with Brown over two days in a rock quarry near Chambersburg, Pa., in August 1859, two months before the raid, Douglass argued that Brown was walking into “a perfect steel trap” and despite Brown’s entreaties, declined to participate. His companion, an escaped slave from South Carolina named Shields Green, decided otherwise. “I believe I’ll go with the old man,” said Green, and ended up being captured, tried, and executed.

Upon first meeting Brown in Canada in 1858, Tubman began helping him plan his raid. She shared her contacts among African Americans and her knowledge of underground connections in Maryland and Pennsylvania. She introduced Brown to several former slaves living in Ontario. She even suggested he should raid Harpers Ferry on July 4.

Though it’s generally thought Tubman was fully committed to participating in Brown’s raid, she disappeared at the crucial moment. Why she failed to join Brown remains a puzzle. Possibly she was gripped by one of her spells. Possibly she had taken on another rescue mission to the Eastern Shore. Or perhaps she finally decided the raid was doomed.

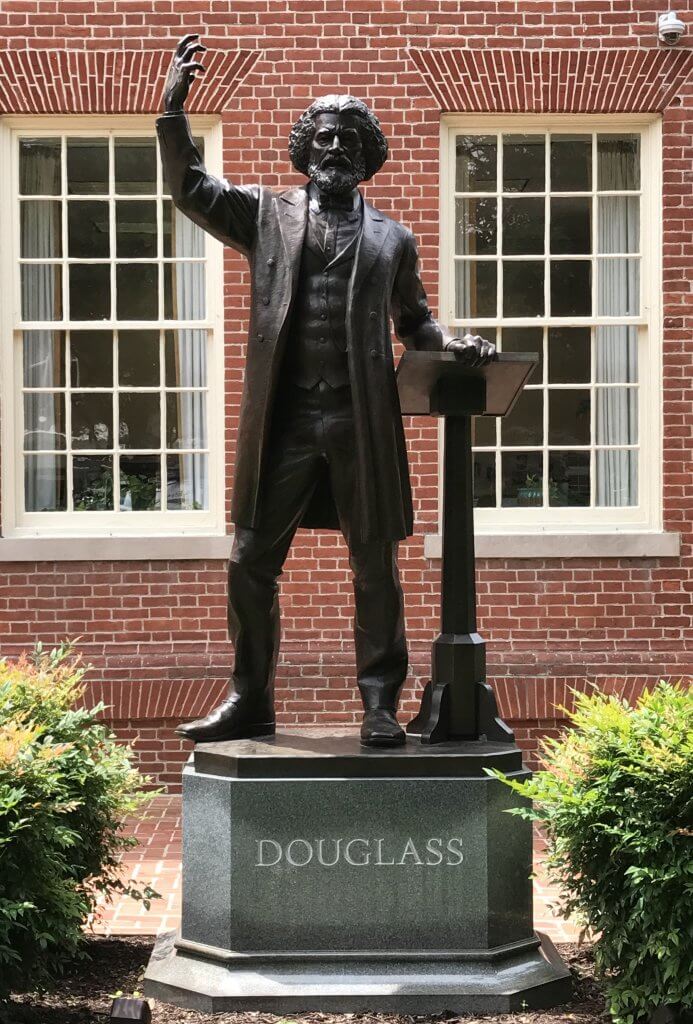

Little remains today to commemorate Douglass’ early years on the Eastern Shore. There’s a historic road marker near the mouth of Tuckahoe Creek and two statues, one in front of the Talbot County courthouse in Easton and the other in the Maryland statehouse in Annapolis.

Quite the opposite, however, for Tubman! Monuments to her are scattered across Dorchester and Caroline counties and in Delaware from Sandtown to Wilmington—a tidy little museum in Cambridge, the Underground Railroad State Park and Visitor Center adjacent to the Blackwater National Wildlife Refuge, a mural on Route 50 near the Choptank River bridge, another mural behind the Cambridge museum, and the 125-mile Underground Railroad driving tour. There’s also a statue of Tubman in the Maryland State House.

I am drawn to two locales associated with Tubman. The Bucktown store stands as it did when teenager Minty Ross’ head was struck by a heavy piece of metal hurled at another slave. Its single room is dim and brown and musty, and one might sit quietly for much of an hour to conjure up Harriet, the other slave, the slaveowner, and the proprietor as Harriet suffered her grievous injury.

The second, called “Red Bridges,” is just north of Greensboro, in Caroline County This is a ford across the upper reaches of the Choptank River, where Tubman helped runaways wade the river in secret on their harried rush toward the Delaware border. At Red Bridges in early spring these days, eager anglers stand shoulder-to-shoulder to hook yellow perch during their spawning run, with little inkling of the historic past of this hallowed setting.

Cover photo: Harpers Ferry National Historical Park.

Credit: Dukeofwild, ownwork, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

All other photos: Gren Whitman