I saw a Delmarva fox squirrel once — two, actually, on the same day. This was a very big deal, because it was 1993, and the Delmarva fox squirrel (Sciurus niger cinereus) was an endangered species.

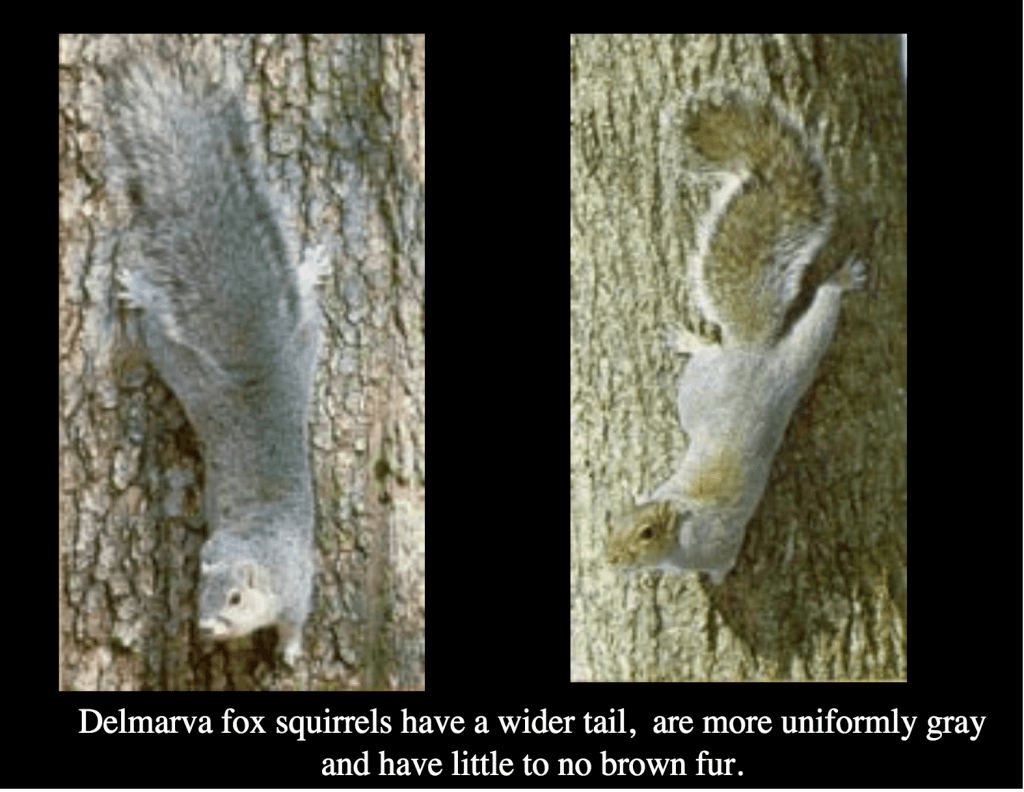

My husband and I were bicycling the Wildlife Drive at Blackwater National Wildlife Refuge in Dorchester County. Bicycling is a great way to slow down and see things you’d miss if you were in a car. And we saw this giant silver grey squirrel with an enormous bushy tail. Even though we’d never seen one before, there was no question that this was a Delmarva fox squirrel. And if that wasn’t enough, then we saw a second!

Delmarva fox squirrels are shy creatures. They live in forested areas and woodlots, not in suburban areas like their abundant cousins, Eastern grey squirrels, so they’re not a familiar sight. They eat mast (acorns, etc.), pinecone seeds, and corn, so it’s handy if there’s a farm field nearby. They nest in trees, but hang out on the ground. They can grow to 30 inches long, but half of that will be a fluffy, bushy tail. (That’s where the fox part of their name comes from — their foxy tail.)

Historically, Delmarva fox squirrels were found on the entire Delmarva Peninsula, plus southeast Pennsylvania, and even (some say) in southern New Jersey. But by the early 1900s, development was starting to claim much of their preferred habitat. And by mid-century, agriculture and logging decreased mature pine and hardwood forests to a fraction of their historic coverage. Overhunting further decimated the population.

In 1945, the Maryland Department of Natural Resources was concerned enough to purchase land that became LeCompte Wildlife Management Area (WMA) in Dorchester County for a Delmarva fox squirrel refuge and study area. This ensured there would be at least one 485-acre area of mature oak and loblolly pine forests on the shore where the squirrels could survive and where biologists could experiment with building populations.

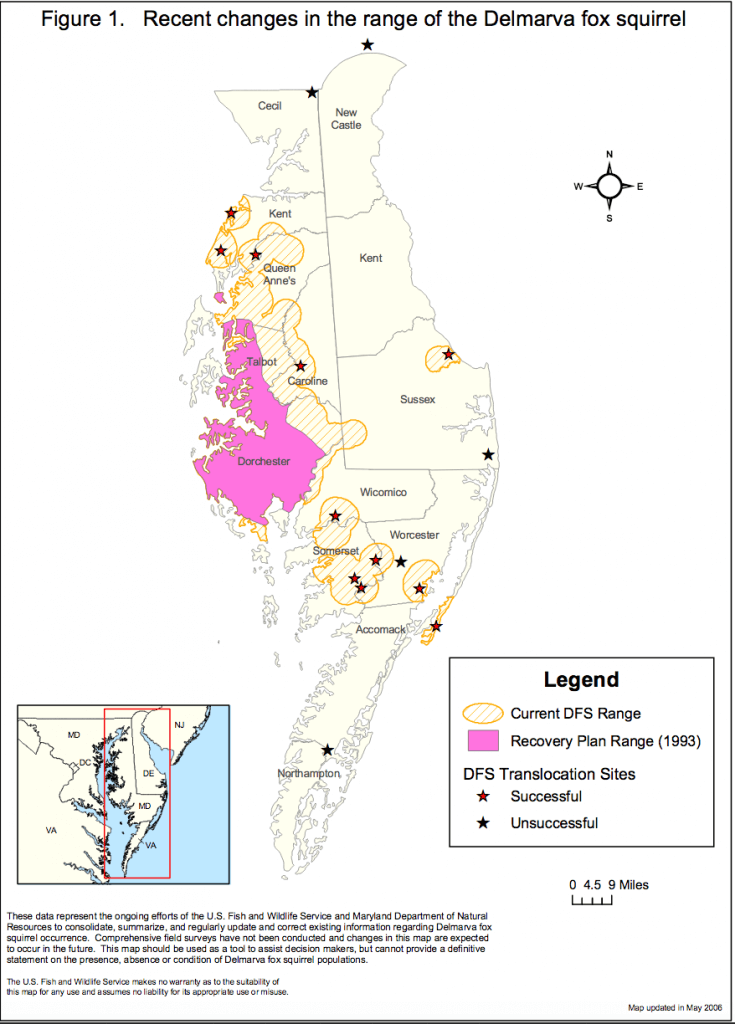

But the population continued to decline. In 1967, the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service (FWS) put the Delmarva fox squirrel on the very first endangered species list. The species had declined to only 10 percent of its historic range, and was located in only four Maryland counties (Kent, Queen Anne’s, Talbot, and Dorchester), and not in Delaware or the Eastern Shore of Virginia.

But by 2015, less than 50 years later, the population had rebounded and spread to such an extent that they were deemed no longer endangered. Today there are an estimated 20,000 Delmarva fox squirrels across 135,000 acres of forest covering 28 percent of the Delmarva Peninsula. Populations exist in all Maryland Eastern Shore counties except Cecil, and in Sussex County Delaware and Appomattox County Virginia. How did that happen?

It took a determined effort and a multi-dimensional approach: protecting habitat, establishing new squirrel populations (and encouraging them to grow and disperse), and closing the hunting season. Because the endangered species list was federal, it was up to the endangered species biologists at the Chesapeake Field Office of the FWS to coordinate the attack. Here are some highlights.

Closing the hunting season (duh!). In 1971, hunting of Delmarva fox squirrels was outlawed. Why it took four years to outlaw hunting of an endangered species is not explained anywhere that I could find. But it was finally done, and a hunting ban is still in effect.

Relocation of animals to establish new populations. Eleven new, thriving Delmarva fox squirrel populations were established through relocating individual animals to new, carefully selected areas (also known as translocating). Their range was significantly expanded in this way.

Squirrels were trapped in various places (Blackwater National Wildlife Refuge, Eastern Neck NWR, LeCompte WMA, Wye Island Natural Resources Management Area, and private farms) and released in areas identified as suitable habitat where the populations would have a good chance of thriving and expanding. The relocated squirrels were monitored to determine whether the new populations would persist. Sixteen relocation attempts were made, involving 264 squirrels; of these, 11 were successful, spreading Delmarva fox squirrel populations to new areas in all three states. Once a population has established, it can spread on its own to contiguous forest areas.

Protecting habitat. Concerted efforts were made to protect large forested areas to preserve Delmarva fox squirrel habitat. This required collaborative conservation efforts between state and federal agencies and private landowners.

As of 2010, about 30 percent of forest occupied by the squirrels in Maryland and Delaware counties was protected from development. Together, public land and conservation easements protected 40,000 acres out of 135,000 total squirrel-occupied acres. There is also protected land into which Delmarva fox squirrel populations can expand.

Four national wildlife refuges provide over 52,000 acres of forested areas suitable for the squirrels in Maryland, Delaware, and Virginia. Blackwater NWR also bought additional woodland in part to increase protected squirrel habitat.

State-owned properties provide almost 100,000 acres of protected forest habitat in the nine Maryland and Delaware counties. Specifically, 11,000 acres of wildlife areas are suitable to support Delmarva fox squirrel populations, in addition to 30,000 acres in state forests and 58,000 acres of Chesapeake Forest Lands.

“We could not have reached this point without the many citizen-conservationists who changed the way they managed their forest lands to make this victory possible.”

Sen. Ben Cardin (D-Md.)

The FWS estimates that 80 percent of the Delmarva fox squirrel habitat is on private land. To help protect this habitat from development, several state programs and private land trusts have worked to secure easements that restrict development on private lands, which in turn preserves habitat. These programs have together preserved close to 150,000 acres of Delmarva fox squirrel habitat. In fact, within the squirrel’s current range, land protection is occurring at a more rapid rate than the rate of development.

Private landowners were a large part of the Delmarva fox squirrel rebound story. The federal government solicited their cooperation, undertaking a strategy of public information and education about improved management practices for preserving habitat on private land. In addition, several programs offered cost-sharing opportunities to private landowners as incentives to implement management practices leading to the restoration or improvement of existing wildlife habitat (prescribed burns, for example).

Eighty percent of the Delmarva fox squirrel range is not vulnerable to sea level rise. Impacts from rising water would be felt most at Blackwater NWR, but biologists feel that the refuge is large enough that the squirrel population would survive by moving inland into adjacent forest area.

“The Delmarva fox squirrel’s return to this area, rich with farmland and forest, marks … a major win for conservationists and landowners.”

-Michael Bean, U.S. Department of the Interior

So, is the Delmarva fox squirrel a conservation success story? Perhaps.

The FWS made a careful, inclusive case for removing the Delmarva fox squirrel from the endangered species list based on science, technology, and research. But objections to delisting came from experts and citizens, and were also based on science and sometimes on the FWS’ own evaluations done during the squirrel’s endangered status. The objections were not enough to sway the decision.

Maryland continues to provide protection to the Delmarva fox squirrel as an animal In Need of Conservation (one whose population is limited or declining in Maryland that may become threatened in the foreseeable future if current trends or conditions persist). The fox squirrel is still on the Delaware endangered species list, and conservation actions to increase and sustain populations in Sussex County continue.

Although it was downplayed in the delisting notice, habitat loss is still the primary threat to the continued existence of the Delmarva fox squirrel, and development pressure on Delmarva peninsula is very strong. One of the criteria for population recovery was the continued maintenance of habitat. While the state and federal lands will continue to provide habitat, the cooperation of private landowners is crucial to Delmarva fox squirrel survival and the squirrels won’t survive without their involvement.

(Note: Thanks to The Princess Bride for the title of this article.)

Further reading:

https://www.fws.gov/northeast/EcologicalServices/pdf/endangered/DPFS2012_5yearreview.pdf